Working Memory

Research and Application of Working Memory and the Effects of Anxiety

The Working Memory Model

Working memory failures happen relatively frequently for everyone [1]. For example, people may forget their pin number they have created just moments ago for a bank account. More critically, nuclear plant operators may fail to follow critical procedures under life-threatening, emergency situations. Such incidents can be attributed to factors such as age, psychological stressors, and emotional anxiety that hinder working memory. It is crucial to understand the how working memory functions to better design interfaces that reduce cognitive load and tackle the limitations of working memory.

Working memory is a limited-capacity system that maintains and stores information in the short term to support complex cognitive tasks such as learning, reasoning, and language comprehension. Baddeley’s model, working memory can be divided into four subsystems: the central executive, the visuospatial sketchpad, the phonological loop, and the episodic buffer [2].

Central Executive

Schneider and Detweiler suggest that the concurrent storage and processing is only one aspect of working memory; the prime function of working memory is the coordination and allocation of resources by the central executive [3]. The central executive is responsible for focusing, dividing, and switching attention and resources to and from its slave subsystems, along with the need to bridge working memory with long-term memory [2]. Miyake et al proposes that the central executive fulfills three basic functions [4]:

- Inhibition - “one’s ability to deliberately inhibit dominant, automatic, or prepotent responses when necessary” [4, P. 57]

- Shifting - rapid, seamless shifting between multiple, concurrent tasks, operations or mental sets

- Updating - refreshing and reconstructing working memory representations

The two storage systems that the central executive coordinates information from is the visuospatial sketchpad and the phonological loop.

Visuospatial Sketchpad

The visuospatial sketchpad is important for many fields, such as architecture and engineering, where visuospatial imagery is key to success. Similarly, the visuospatial components of working memory have played a critical role in scientific discoveries, such as the discovery of the general theory of relativity by Einstein [5]. The visuospatial sketchpad holds encoded, spatial information that is captured from the visual sensory system or retrieved from long-term memory to produce a recollection of an image [6, P. 129]. For instance, architects may use their visuospatial sketchpad to create a mental synthesis of their design, and retain information regarding where each structural component is located.

Phonological Loop

The phonological loop is most likely the simplest out of the quadripartite system and has been investigated most extensively [7]. This system has two components, a phonological store that stores acoustic or speech-based information for a brief period of time (1 to 2 seconds), and an articulatory control process. Its main functions are twofold. 1) It uses subvocal repetition to maintain information within the phonological store, and 2) it uses subvocalization to register visually presented materials in the phonological store. The phonological store plays a crucial role for long-term phonological learning, especially with acquiring foreign languages [7]. This subsystem is susceptible to a number of capacity and recall issues, including:

• Acoustic similarity effect - recalling of ordered items is more difficult if the items are similar in sound. For instance, recalling “man, cap, can, map, mad” is more difficult than recalling “pit, day, cow, pen, rig” [7, P. 558]. Recalling is not affected by semantic similarities of items. • Word-length effect - longer words are more susceptible to recall failure because they take longer to rehearse. Generally, humans can remember about as many words as they can say in 2 seconds [7, P. 558].

Episodic Buffer

The fourth subsystem of the working memory model is the episodic buffer and it is responsible for connecting working memory with long-term memory. The episodic buffer can be thought of as a temporary storage that acts as a global workspace for the central executive. Working memory retrieves information from long term memory by “downloading” the information into the episodic buffer, and proceeds to manipulate and create new representations of the information, rather than simply activating the nodes in the semantic network [2]. According to Baddeley, the episodic buffer is assumed to be accessible to conscious awareness, which then provides convenient bindings for different systems to integrate with working memory.

Limitations of Working Memory - Capacity

In his seminal research, Miller has described the magical number of 7 plus or minus two chunks that represent the capacity limit of working memory [8]. Furthermore, Miller focused on the ability to effectively increase working memory capacity by intelligently “chunking” items together. According to Simon, chunks are a collection of items that have strong ties with each other, but weaker ties with other, concurrent chunks in working memory storage [9]. For example, the following 12 letter sequence “fbicbsibmirs” can be grouped into four chunks, FBI, CBS, IBM, and IRS. Later research and evidence suggest that the limit is substantially fewer, stating that 4 plus or minus 1 is the limit [10].

The practical identification of chunks and forming of associations are dependent on the knowledge stored in long-term memory [10]. During the process of chunking, related concepts within long-term memory are evoked and activated. Activated information is more readily accessible as well, and acts as a supplement to working memory in the form of the phonological buffer or the visuospatial sketchpad [10]. Thus chunks “can be more than just a conglomeration of a few items from the stimulus” [10, P. 92]. In fact, Gobet and Simon found that expert chess players compared to other chess players differ not in the quantity of chunks but in the size of these chunks [11].

Duration

The capacity limits of working memory are closely tied to the time constraints of working memory. Information in working memory will be lost if the chunks are not periodically reactivated through the process of maintenance rehearsal. During this process, one continuously thinks of this item over and over and thereby refreshing the information in storage. For acoustic information, this rehearsal is in the form of a series of subvocal articulation that occurs in the phonological loop, and is subject to a number of factors that can impair rehearsal, including word-length effects and acoustic similarity effects. According to Card, Moran, and Newell the half-life of chunks is estimated to be approximately 70 seconds for one chunk and 7 seconds for three chunks [12].

Attention

Working memory has a limited supply of attentional resources. Processing and maintaining information rely on the same pool of resources and no two concurrent tasks can be attended to simultaneously [13]. If attention is fully consumed by a concurrent task, the strength of the unattended information will suffer from a time-based decay; a reactivation is necessary before the memory trace is completely lost. According to the time-based, resource-sharing model, “sharing of attention is achieved through a rapid and incessant switching of attention from processing to maintenance” [14, P. 571]. High cognitive load is therefore the behavior in which tasks impede switching by continuously demanding attentional resources and preventing the central executive to perform executive functions such as maintenance rehearsals. On the other hand, cognitively less demanding tasks allow for frequent pauses and switching to other concurrent tasks [13].

The Effects of Anxiety

Anxiety can have a disruptive effect on working memory. Eysenck, Derakshan, and Santos define anxiety as an emotional and motivational state occurring in threatening situations, in which individuals are unable to instigate a clear behavioral pattern to remove the threat [15]. Individuals often try to develop strategies to reduce anxiety in order to achieve a certain goal, and are often times worried about the threat itself. Anxiety itself has adverse effects on the cognitive performance; in fact, the right amount of anxiety can boost performance, whereas any amount further will become detrimental to cognitive performance [15].

The processing efficiency theory was developed by Eysenck and Calvo to explain the effects of anxiety on cognitive performance effectiveness and efficiency [16]. According to the theory, worrisome thoughts impacts the central executive by consuming cognitive resources of working memory, leaving less available resources for other concurrent tasks. Any task that has substantial demand on working memory storage and processing will be most vulnerable to high performance impairments due to anxiety. Detrimental effects are also expected in the phonological loop because worry typically involves subvocal speech activity [17].

Attentional control theory posits that anxiety disrupts the balance between two main types of attentional systems: a top-down, goal-driven system and a bottom-up stimulus driven system [15]. The top-down control of attentional system is influenced by metacognitive factors such as expectations and goals. The bottom-up system is involved in the bottom-up control of attention through the signal detection of sensory events, especially those that are salient or unexpected. Under stressful conditions when anxiety is high, the bottom-up, stimulus-driven system is given more weight in terms of influence. Anxiety affects the bottom-up system via automatic processing of threat-related stimuli, resulting in a decrease in the influence of its counterpart, goal-directed attentional system [15]. Attention is then shifted from task-relevant processes to task-irrelevant ones (e.g. threat related distractors, worrisome thoughts) and so impairs processing efficiency.

Interestingly, there are a number of research studies that have shown high anxiety groups to outperform none to lower anxious groups [18]. According to attentional control theory, the reason is because anxiety impairs efficiency more than performance effectiveness. Furthermore, worry can instigate motivation to lessen anxiety and potential performance impairments can be mitigated [15].

Case Study

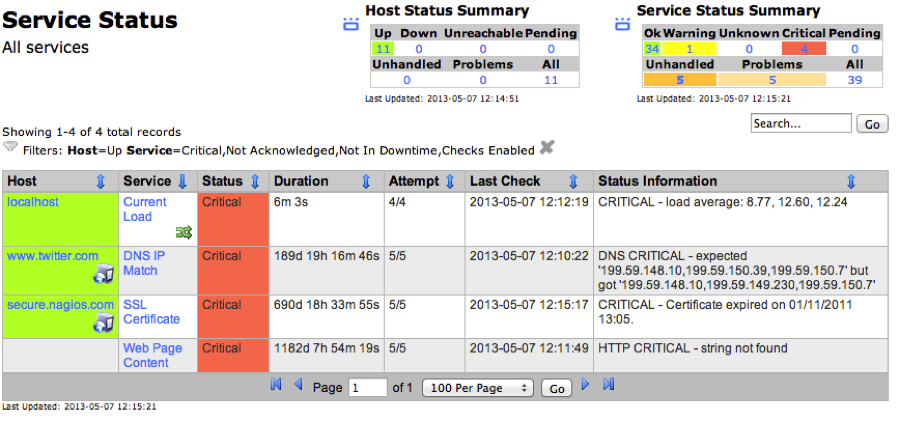

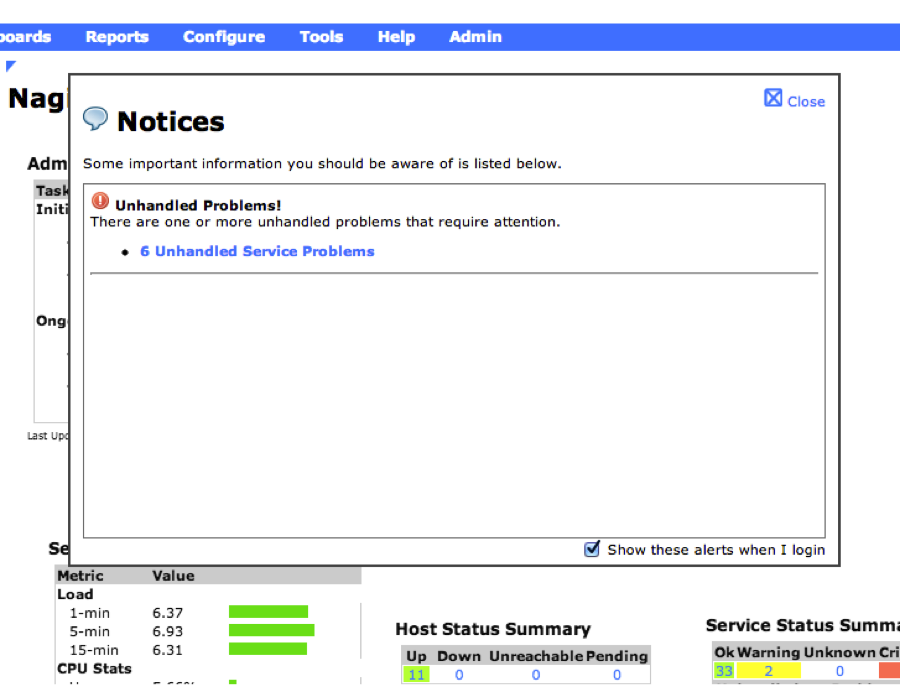

A website may go offline due to a denial-of-service attack. It is then the responsibility of system admins to detect the threat, locate the issue, and mitigate the attack. The first tool admins may use is an IT infrastructure-monitoring tool such as Nagios. From CPU usage statistics to network host summaries, Nagios provides all the necessary information for a system administrator. However, under cognitive load, system administrators may perform suboptimally due to anxiety and pressure.

Nagios is designed so that any critical issues or warnings are fully apparent in the interface (figure 1). When a user first logs on, a popup is shown with the number of critical incidents that need to be attended to (figure 2). This gives a clear path of action for the admin that aligns well with the admin’s goal of removing the threat, and moreover putting the site back online. The admin can also consult the network status map to view the network topology diagram. This is helpful because it removes the need to mentally synthesize the network and its intricacies in the visuospatial sketchpad.

During emergency situations, the anxiety and pressure would cause the attentional resources of the central executive to be consumed by task-irrelevant, distracting tasks, such as worrisome thoughts of losing customers and revenue. The phonological loop would be occupied with the same thoughts as well in the form of subvocal speech. Less time is spent with maintenance rehearsals, and therefore chunks in working memory, information that is crucial to diagnosing the problem, become more susceptible to loss and time-decay.

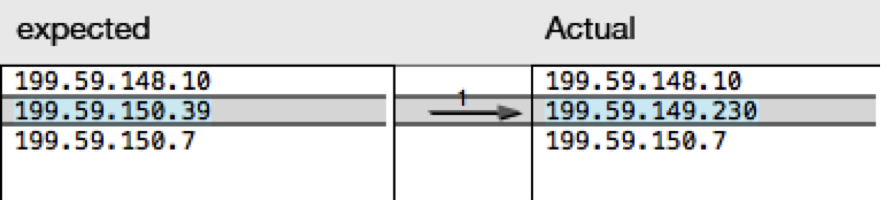

A number of improvements can be made to the interface. During critical events, it is important to reduce memory load of the user and any methods to offload information in working memory is of value. Nagios can improve the interface by providing a textbox column in the service status table, in which the admin can take notes per incident. This removes the need for the admin to retain all diagnostic information in working memory. IP address comparisons under status information incurs cognitive load because of the need to sequence between each string. It is recommended to display a side-by-side comparison chart instead, similar to what programmatic diff-tools output (figure 3).

Conclusion

Working memory is the limited capacity system of the human brain that is acts as a cognitive workspace. It bridges the bottom-up sensory systems with top-down cognitive systems and interfaces with long-term memory. It is subject to various limitations and recall issues, including limitations of capacity, duration, and attentional resources. Designers should leverage this knowledge to design interfaces that reduce cognitive load and tackle the limitations of working memory.

References

- [1]D. L. Schacter, The Seven Sins of Memory. 2001.

- [2]A. Baddeley, “Working memory: looking back and looking forward.,” Nature reviews. Neuroscience, vol. 4, no. 10, pp. 829–39, Oct. 2003.

- [3]W. Schneider and M. Detweiler, “A Connectionist / Control Architecture for Working Memory,” \ldots OF LEARNING&MOTIVATION: V21, 1988.

- [4]a Miyake, N. P. Friedman, M. J. Emerson, a H. Witzki, a Howerter, and T. D. Wager, “The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex ‘Frontal Lobe’ tasks: a latent variable analysis.,” Cognitive psychology, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 49–100, Aug. 2000.

- [5]B. Ghisilen, The Creative Process. 1952.

- [6]C. D. Wickens, An Introduction To Human Factors Engineering, Second Edi. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc., 2004, p. 587.

- [7]A. Baddeley, “Working Memory,” Science, 1992.

- [8]G. Miller, “The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information,” The psychological review, 1956.

- [9]H. A. Simon, “How big is a chunk,” Science, 1974.

- [10]N. Cowan, “The magical number 4 in short-term memory: a reconsideration of mental storage capacity.,” The Behavioral and brain sciences, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 87–114; discussion 114–85, Feb. 2001.

- [11]F. Gobet and H. A. Simon, “Templates in Chess Memory: A Mechanism for Recalling Several Boards,” 1996.

- [12]S. Card, T. Moran, and A. Newell, “The model human processor,” Ariel, 1986.

- [13]P. Barrouillet, S. Bernardin, S. Portrat, E. Vergauwe, and V. Camos, “Time and cognitive load in working memory.,” Journal of experimental psychology. Learning, memory, and cognition, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 570–85, May 2007.

- [14]P. Barrouillet, S. Bernardin, and V. Camos, “Time constraints and resource sharing in adults’ working memory spans.,” Journal of experimental psychology. General, vol. 133, no. 1, pp. 83–100, Mar. 2004.

- [15]M. W. Eysenck, N. Derakshan, R. Santos, and M. G. Calvo, “Anxiety and cognitive performance: attentional control theory.,” Emotion, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 336–353, 2007.

- [16]M. W. Eysenck and M. G. Calvo, “Anxiety and performance: The processing efficiency theory,” Cognition & Emotion, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 409–434, 1992.

- [17]R. M. Rapee, “The utilization of working memory by worry,” Behaviour Research and Therapy, vol. 31, pp. 617–620, 1993.

- [18]A. Byrne and M. W. Eysenck, “Trait anxiety, anxious mood, and threat detection,” Cognition & Emotion, vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 549–562, 1995.