Prior Knowledge

Research and Application of Schemas, Semantic Networks, and Affordances

What is Prior Knowledge

Prior knowledge plays a critical role in human cognitive tasks. When information is perceived from sensory inputs, top-down processing aids the brain in attaching meaning to what is sensed. Prior knowledge is stored in long-term memory and guides the mind to a course of action. Past experiences also aid in processing and understanding signals that are too weak or degraded to be efficiently perceived, such as the classic example of a doctor’s handwriting. Although words may be illegible, expectations of sentence structure and vocabulary allow the top-down cognitive process to guess the word and “fill in the blank” correctly. These expectations are based on how frequent humans encountered the event in the past and the context in which the stimulus was perceived [1, P. 125].

Psychologists have developed numerous theories that model how knowledge is structured and organized in long-term memory. These include schema theory and semantic networks. This paper will review the research literature behind the models, discuss the effect of prior knowledge on human factor design, and apply the research to a case study.

Schema Theory

The information stored in long-term memory is actively organized around central concepts known as schemas. Schemas are built from the interaction with the environment to organize experience and are mental representations of objects, events, or people [2]. When an external stimulus is perceived, humans try to make sense of the input in terms of stock schemas stored in long term memory. This process of linking incoming information with prior knowledge is called assimilation [3].

Assimilation is one aspect of the learning process. Piaget suggests that learning is guided by the organization of schemas and the adaptation of schemas, which include the “assimilation of new information into existing schemas, or the accommodation of schemas to new information, which may not fit into existing schemas” [4]. Thus, a schema can change over time as needed. Knowledge is also linked to an action schema, and usually entails the expectation of particular responses. In Schmidt’s term, this is called a recall schema and is defined as the schema in which motor movements are mapped with the actual outcomes [5]. In a similar sense, the act of recalling a story is done by relating the experience to one’s set of familiar schemas rather than from rote memorization of details [2].

What pushes learning is what Piaget describes as Equilibration. Equilibration is the force that drives cognitive development. When new information is captured through sensory inputs, but cannot be assimilated into the stock schemas in our long-term memory, equilibration forces the learning process to mold current schemas to accommodate the new information and bring balance [6]. When there is a one to one mapping between new material and stock schemas, it is said to be intuitive. On the other hand, if the effort of accommodation is substantial, rejection can occur. Thus designers are recommended to avoid applying design patterns that make accommodation difficult.

Semantic Networks

The larger collection of interrelated schemas is called a semantic network [7]. Each schema stored in long-term memory can be thought of as a node in a network. Related nodes are connected by links and a connection between two nodes denotes an association of information. Collins and Quillian first suggested that a semantic network was structured in a tree-structured hierarchy, with “connections determined by class-inclusion relations” [8]. Although economical, this type of structure is severely limited because it can only deal with inheritance-based categorization of typical objects [9].

Instead of the tree-structure, typical textbooks and later research show a network with an arbitrary set of nodes and connections with no structure. A node, or concept is defined by what it is connected to. According to researchers, this seemingly arbitrary network structure exhibits certain characteristics. Similar to other natural networks, semantic networks possess 1) a small-world structure arising from a 2) scale-free organization. In other words, nodes are organized into neighborhoods, hubs, and the distance between two seemingly unrelated nodes is short on average [9].

During a recall of information, certain nodes are activated. Activation in one node can trigger the activation of other nodes connected along network links. Anderson and Pirolli call this spreading activation [10]. Spreading occurs near instantaneously, but the activation strength will decay exponentially with distance. Theories such as ACTE and ACT* are just some of the theories that model spreading activation.

Certain characteristics determine how well prior knowledge is recalled from long-term memory. One characteristic is strength. Strength is determined by how recently information was used, as well as how frequently the node was activated. Frequency is directly proportionate to the number of links connected. The more connections, the greater the chances are of activation, and therefore a likely increase in strength. This is because “activations converging on a node from multiple sources will sum” [10, P. 794]. In other words, memory retrieval will often fail due to weak strength, weak or few associations with other information, and or presence of interfering associations.

Priming

The notion of activation is also tied to the effect of priming. Priming is the “facilitated identification of perceptual objects from reduced cues as a consequence of a specific prior exposure to an object” [11]. In terms of semantic networks, prior activation of nodes enhances the ability to process subsequent stimuli in a certain fashion related to the activated neighborhood. Humans tend to see things related to the priming stimuli. For instance, when humans enter a kitchen, the “kitchen” schema is brought forth and nodes linked to it, such as “furniture” and “sink”, are activated with a high probability. Thus we expect to find objects such as a dining table or a refrigerator in a kitchen instead of unrelated objects such as a motor vehicle. Ratcliff and McKoon found that as the network distance between the prime and the target decreased, the facilitative effect of a prime on target recognition increased [12]. In fact, the effect of priming decays exponentially as a function of distance [13].

Priming effects can occur in individuals who have brain damage. This leads to show that priming is separate from the brain mechanism responsible for recollecting past, episodic memory. Such is the case for amnesic patients who can demonstrate effects of priming after encountering certain words or objects [11]. Priming can also occur without consciousness and operates at a pre-semantic level of processing that does not involve access to the meanings of words or objects [11].

Priming is an effective tool for human factors design. Designers can take advantage of the effect to influence user behavior and thought process. For example, the designer may opt to use the word “patients” instead of “customers” in a dental software program to predispose the secretary to think in a care giving, and not a business, perspective. However, if the incorrect schema is instantiated through priming, misunderstanding and confusion can ensue. Such is the case with the Stroop effect [14].

Metaphors

Many psychologists have suggested that metaphors play a special role in how humans organize conceptual knowledge. Metaphor-based schema is “the representational structure that maps knowledge about a conceptual metaphor’s vehicle domain onto its topic domain” [15, P. 613]. It can be thought as a memory aid for learning new knowledge through the interaction of two different domains. Gibbs suggests that metaphoric expressions are constructed from available cognitive mappings stored in long-term memory [16].

Metaphors are a common tool used in interface design. A classic example is the metaphor of desktops used in operating system GUIs. Virtual files on the desktop can be placed into folders to organize and categorize, just as physical paperwork can be organized in file cabinets. Other metaphorical examples found in software design include magnifying glasses to represent zoom or search, trash icons for delete, and national flag icons for language selection.

Affordance

When a metaphor is applied to an object, it is said that the metaphor brings with it, a set of affordances. Affordances are inherent properties of an object that allows an actor to perform an action. For example, a knob on a door affords ‘twistability’ and the door affords ‘openability’. According to Gibson, affordances are independent of the user’s ability to perceive the properties [17]. Affordances are also relative to the capabilities of the user. For instance, a staircase affords ‘climbability’ to an adult, but not to a toddler who is not tall enough to reach the first step.

In contrast to Gibson’s view, Norman’s definition of affordance is defined in terms of both real and perceived affordances. According to Norman, an affordance suggests a strong cue to its operation. Thus when both real and perceived are linked, affordance emerges and the user knows how to use the object without labels or explanation [18]. In terms of Norman’s view, a hidden door would not have an affordance of ‘openability’ because the user does not perceive the existence of the door. Affordance is therefore dependent on the experience, culture, and prior knowledge of the actor.

The two different definitions of affordance have caused confusion in the HCI community [19]. Realizing that the ambiguity of the term would further spread the misuse, McGrenere and Ho have further solidified the concept of affordance by extending Gibson’s definition. One such clarification is that affordances do not always map one to one to system functions because affordances are often nested within other properties. For example, the ‘margin adjustability’ of a text editor is within the parent affordance of ‘document editiability’. This aligns with Gaver’s research on nested and sequential affordances [20].

Gibson states that affordance is binary; the property either exists, or doesn’t. Warren however, demonstrated that there is in fact, an optimal point in which the user can act upon the affordance with ease [21]. His experiment with stair ‘climbability’ showed that people’s visually guided judgments of ‘climbability’ accurately reflected a U-shaped function relating work to riser height and leg length (π=R/L). Affordances are therefore not binary, as Gibson suggests. Instead, there is a difficulty range for the affordance. Designers should strive to design elements that achieve the optimal point, π_optimal.

Application of Research

Tesla.com’s “Go Electric” is a section that aims to answer frequently asked questions in an interactive manner. It is analyzed here in terms of McGrenere and Ho’s extended definition of Gibsonian affordance.

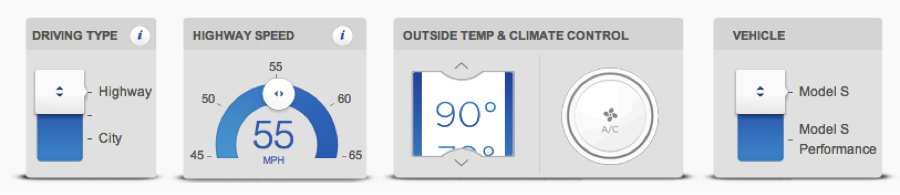

The mileage calculator has four types of design patterns that control mileage-altering variables: slides (driving type, vehicle), dials (highway speed), scrollers (temperature), and buttons (climate control). Each pattern provides certain affordances through the use of metaphors. For instance, the raised-looking knob within the blue, vertical track reminds the user of a physical slide switch, which brings forth the affordance of ‘slideability’. The highway speed dial in the shape of a speedometer is also an excellent use of metaphor. The user can easily recognize what the dial controls (speed). The knob also has a style that affords ‘slideability’

The A/C button’s label and the fan icon above act as a priming mechanism to activate the schema of climate control. In fact, the entire website, with images of cars, roads, and dashboards activate the nodes within the semantic network related to motor vehicles. Thus when the user views the A/C button, the user understands its reference to the climate control system of a Tesla car, and not to that of a desk fan.

Aforementioned affordances are all nested under the parent affordance of ‘function invokeability’. It is also important to distinguish between the underlying affordance of the controls from the information that specifies the affordance [19]. The affordance of mileage adjustability, and nested within it, slideability, pressability, and scrollability all exist regardless of the user’s perception and knowledge of them. The shape and style of the controls are the graphical vehicles that transport the affordance information to the user.

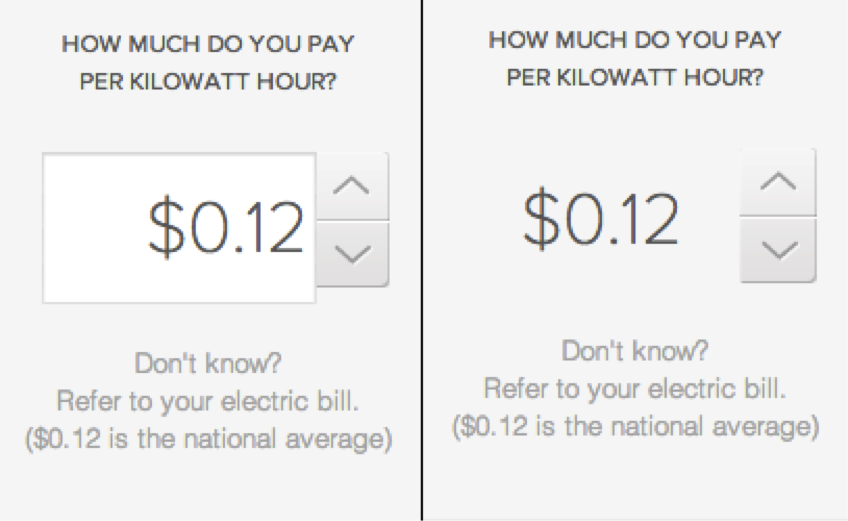

The “How much do you pay per kilowatt hour” number spinner on the charge time and cost calculator is one design that fails to clearly specify the underlying affordance to the user. The design has two components: buttons that adjust the variable and a box that displays the monetary value. The design fails because the slightly depressed style of the box is indicative of an editable input box and invites users to click-and-edit, even though the field is read-only. There are no actionable affordances, yet the design looks as if it does. In Gaver’s term, this is a false affordance and signifies a sub-optimal π value. An alternative design is shown below.

Conclusion

Prior knowledge plays a critical role in human cognitive tasks. Schemas and semantic networks are two models that map cognitive knowledge in the brain. Leveraging the facilitative effects of priming and metaphors can make designs intuitive and help the user assimilate or accommodate new information more easily. However, if the incorrect nodes of the semantic network are activated, designs can become difficult to comprehend and lead to abandonment. Designers should strive to design interfaces in a way that matches the user’s expectation and the affordances of the interfaces should provide actions that help the user meet their goals.

References

- [1]C. D. Wickens, An Introduction To Human Factors Engineering, Second Edi. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc., 2004, p. 587.

- [2]M. A. Arbib, “Schema Theory,” Encyclopedia of artificial intelligence, 1992.

- [3]J. Piaget, Play, dreams and imitation. 1962.

- [4]P. a. Chalmers, “The role of cognitive theory in human–computer interface,” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 593–607, Sep. 2003.

- [5]R. A. Schmidt, “The Schema as a Solution to Some Persistent Problems in Motor Learning Theory,” Motor Control: Issues and Trends, pp. 41–65, 1976.

- [6]J. Piaget, The development of thought: Equilibration of cognitive structures. B. Blackwell, 1978.

- [7]D. E. Rumelhart and A. Ortony, “The representation of knowledge in memory,” Center for Human Information Processing, pp. 99–135, 1976.

- [8]A. M. Collins and M. R. Quillian, “Retrieval Time from Semantic Memory,” Journal of verbal learning and verbal behavior, vol. 2, 1969.

- [9]M. Steyvers and J. B. Tenenbaum, “The large-scale structure of semantic networks: statistical analyses and a model of semantic growth.,” Cognitive science, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 41–78, Jan. 2005.

- [10]J. R. Anderson and P. L. Pirolli, “Spread of activation.,” Journal of \ldots, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 791–798, 1984.

- [11]D. L. Schacter, “Priming and Multiple Memory Systems: Perceptual Mechanisms of Implicit Memory,” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 244–256, Jul. 1992.

- [12]R. Ratcliff and G. McKoon, “Does activation really spread?,” Psychological review, vol. 88, pp. 454–457, 1981.

- [13]J. R. Anderson, “A Spreading Activation Theory of Memory,” Journal of verbal learning and verbal behavior, 1983.

- [14]C. M. MacLeod, “Haifa Centuryof Researchon the Stroop Effect: An Integrative Review,” Psychological Bulletin, vol. 109, no. 2, pp. 163–203, 1991.

- [15]G. McKoon and R. Ratcliff, “Priming in Item Recognition: The Organization of Propositions in Memory for Text,” Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 1980.

- [16]R. W. Gibbs, “Categorization and metaphor understanding,” Psychological review, pp. 572–577, 1992.

- [17]J. J. Gibson, “The theory of affordance,” Perceiving, Acting and Knowing, pp. 67–82, 1977.

- [18]D. A. Norman, “Affordance, Concentions, and Design,” interactions, pp. 38–42, 1999.

- [19]J. McGrenere and W. Ho, “Affordances: Clarifying and evolving a concept,” Graphics Interface, no. May, pp. 1–8, 2000.

- [20]W. W. Gaver, “Technology Affordances,” \ldots in computing systems: Reaching through technology, 1991.

- [21]W. H. Warren, “Perceiving affordances: Visual guidance of stair climbing,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, vol. 10, pp. 683–703, 1984.